I must mention that though the learned advocate appearing on behalf of the Plaintiff canvassed arguments to the effect that the author of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” is the grandmother of the Plaintiff - JANVI and not JANVI herself, none of the documents or pleadings in the Plaint support her case. In view of the detailed discussion set out earlier in this judgment I am clearly of the view that the Plaintiff has approached this Court with a completely false case. These entire proceedings are nothing short of an abuse of the process of the Court. I have no hesitation in saying that these proceedings have been filed only to try and extract monies from the Defendant. It's what I would call a nuisance litigation. The Plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding in the above Suit and I find no other compelling reason why the above Suit cannot be disposed of before recording oral evidence. I am, therefore, clearly of the view that the Defendant is entitled to a summary judgment of dismissal of the above Suit under the provisions of Order XIII-A of the CPC. {Para 30}

In the High Court of Bombay

(Before B.P. Colabawalla, J.)

Interim Application (L) No. 6771 of 2020

In

Commercial (IP) Suit No. 242 of 2015

In the Matter Between

Jayant Industries Vs Indian Tobacco Company .

Decided on January 11, 2022,

Citation: 2022 SCC OnLine Bom 64 : (2022) 89 PTC 255 : (2022) 4 AIR Bom R 641

The Judgment of the Court was delivered by

B.P. Colabawalla, J.:— The present Interim Application is filed by the Defendant seeking the following reliefs:—

“(a)(i) this Hon'ble Court be pleased to dismiss the Plaintiff's claim for copyright infringement under Order XIII-A of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908, as applicable to Commercial Suits.

(ii) this Hon'ble Court be pleased to dismiss the Plaintiff's claim for passing off under Order XIII-A of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908, as applicable to Commercial Suits.

(b) In the alternative to the above prayer clause (a), this Hon'ble Court be pleased to direct the Plaintiff to deposit sufficient monies in this Hon'ble Court to cover the costs and expenses of the Defendant in defending the suit, or give adequate security for restitution of costs and expenses under the provisions of Order XIII A of the Civil Procedure Code as applicable to Commercial Courts”.

2. To put it in a nutshell, what the Defendant seeks is a judgment of dismissal of the above Suit under the provisions of Order XIII-A of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 (for short “the CPC”) and, in the alternative, a direction to the Plaintiff to deposit sufficient monies in this Court to cover the costs and expenses of the Defendant in defending the captioned Suit.

3. The application is filed for dismissal on the ground that based on the documents relied upon by the Plaintiff herself [JANVI SHAH (for short “JANVI”) and who is the sole proprietor of JAYANT INDUSTRIES], she has no real prospect of succeeding on either claim made in the Suit and there is no compelling reason justifying the non-disposal of the claims of the Plaintiff before the recording of oral evidence. In other words, it is the case of the Defendant that the claim made in the present suit does not have any real prospect of succeeding. It is a highly fanciful claim and has been made only to harass the Defendant. Though the suit is instituted in the name of the sole proprietary concern of JANVI i.e. JAYANT INDUSTRIES, I shall refer to the Plaintiff as JANVI. Similarly, any reference to the Plaintiff in this judgment shall mean JANVI.

4. On perusing the prayers in the Plaint, the reliefs sought, are for perpetual injunctions restraining the Defendant from in any manner using in relation to cigarettes or any other product/s, the impugned trademark, or any other trademark identical with and/or deceptively similar to the Plaintiff's trademark and copyright “CLASSIC” so as to infringe the Plaintiff's registered copyright as well as an action in passing off.

5. Apart from the perpetual injunctions, JANVI has also sought a money decree in the sum of Rs. 2,100 crores by way of damages and/or royalty, or in the alternative, the Defendant render true and faithful accounts in this Court of all the profits earned by the Defendant by using the impugned trademark and copyright “CLASSIC” and to pay such amount as this Court deems fit, together with interest @ 12% per annum till payment and/or realization.

6. JANVI has come to Court with a case that JAYANT INDUSTRIES was initially established as a partnership firm between Mrs. Damayanti Kantilal Shah (grandmother of JANVI) and her husband Mr. Kantilal G. Shah (grandfather of JANVI). Mrs. Damayanti Shah continued to act as a partner of the said firm till her retirement in the year 1982 and upon retirement gave her stake to Mr. Jayant Kantilal Shah, who is the father of JANVI and also her constituted attorney. The other original partner, Mr. Kantilal G. Shah, during his lifetime, gave his entire stake in JAYANT INDUSTRIES directly to JANVI in the year 2007. It is, therefore, stated that JANVI's concern is thus in business for the last several generations spread over decades since 1968 and have continuously expanded and grown its business in and outside India. It is thereafter stated that JANVI is the owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” written in a characteristic style, of which the word “CLASSIC” forms an essential and prominent part. JANVI has applied for copyright registration vide its application dated 11th June 2012 and secured registration under the Copyright Act, 1957 for the said artistic work on 13th August 2013. It is stated that the registration is granted after complying with the procedure laid down in law and is subsisting and valid till date. It is important to mention that JANVI, who claims to be the sole proprietor of the Plaintiff, was admittedly born on 21st April 1987. She was, therefore, approximately 28 years old at the time of instituting the above Suit. Be that as it may, it is thereafter stated in paragraph 9 that sometime in the year 1968, the Plaintiff, namely JANVI, conceived and adopted the suit trademark “CLASSIC” in respect of its various products and services for sanitary preparations, ash-trays, room fresheners etc. The Plaintiff applied for registration of the label mark (artistic) on 25th April 2012 and the mark is pending registration. It is thereafter again reiterated that JANVI manufactures various types of sanitary and perfumery products like multi-purpose air purifiers, plastic dispensers for rooms, cupboard purifiers, etc. as also cigarettes and cigar ash-trays etc. It is reiterated that the Plaintiff has used “CLASSIC” as an umbrella brand for its various products since the year 1968 and has been openly, continuously, extensively, and exclusively using the trademark/logo “CLASSIC” in respect of its products and services all over India. It is thereafter stated that it has significant presence all over India and even exports its products. In support of this contention, copies of some invoices/bills pertaining to the sale of products by the Plaintiff under the brand name “CLASSIC” right from the year 1968 to date are annexed at Exhibit-C to the Plaint. According to JANVI, the trademark “CLASSIC” has become popular and is a household name and this is apparent from the Plaintiff's volume of annual sales of around Rs. 38 Lakhs (wrongly mentioned in the Plaint as Rs. 38 Crores) for the products bearing the trademark “CLASSIC”. It is stated that the Plaintiff has spent and continues to spend large sums of money towards publicity and sales promotional efforts carried out to popularize, publicize and promote the sale of its products under the trademark “CLASSIC”. The total sales figures are also set out in a statement certified by the Chartered Accountant, which is annexed at Exhibit-D to the Plaint.

7. In a nutshell, it is the case of JANVI that the Plaintiff is active in this business for more than five decades and enjoys reputation of premium standards and outstanding quality for its various products all of which have been continuously sold under the trademark “CLASSIC”.

8. It is for this reason that JANVI was thus shocked when it came to her notice that the Defendant has blatantly copied the trademark “CLASSIC” for cigarettes manufactured and sold by it. Since the Defendant had adopted the word “CLASSIC” without any consent, authorization, or license of the Plaintiff, which according to the Plaintiff, is identical to its trademark, had indulged in acts amounting to violation of the Plaintiff's right in its copyright and trademark. In the Plaint, it is stated that the Defendant has deliberately adopted and is using the trademark and copyright logo “CLASSIC” for promotional/marketing purposes with a definite and mala fide intention of deriving unlawful benefit and to trade upon and take advantage of the hard-earned reputation and goodwill acquired by the Plaintiff through its trademark. The Plaintiff having used the trademark “CLASSIC” for ash-trays which is a related/ancillary product, there is a clear intent on the part of the Defendant to ride on the goodwill earned by the Plaintiff in the said trademark “CLASSIC” which consumers of cigarettes have come to acknowledge as a quality product and associate with that of the Plaintiff's product.

9. Thereafter, the Plaint sets out certain correspondence between the Plaintiff and certain officials of the Defendant whereby the Plaintiff wanted to sell her copyright to the Defendant, but which was without any success. It was in these circumstances that the Suit is filed and a claim for seeking perpetual injunctions against the Defendant as well as a claim of Rs. 2,100 Crores is made by way of damages.

10. In this backdrop, Mr. Kadam, the learned Senior Counsel appearing on behalf of the Defendant, submitted that the claim made by the Plaintiff is not only highly fanciful, but wholly unsustainable. He pointed out that the Defendant is a registered proprietor of the trademark “CLASSIC” (97 registrations) in Class 34 and has openly and extensively been advertising and marketing cigarettes bearing the trademark “CLASSIC” written in a stylized manner since 1979. The trademark “CLASSIC” has immense goodwill in the market and the purchasers identify “CLASSIC” cigarettes exclusively with the Defendant. To substantiate this argument, Mr. Kadam pointed out that the Defendant's gross sales for cigarettes sold under the “CLASSIC” trademark since 1994 to 2019 is Rs. 21,068.12 Crores and in the Financial Year 2018-2019 alone, was Rs. 3,200 Crores. Further, he submitted that the Defendant is the registered Proprietor of 97 trademarks in Class 34 comprising of the word “CLASSIC” (written in a stylized form). He also brought to my attention the list of the said trademarks which are annexed at Exhibit-B to the Interim Application. He submitted that in the Plaint it is JANVI's case that she is the author and owner of the copyright comprised in the artistic work “CLASSIC” and of a prior proprietorship of the trademark “CLASSIC”. This is required to be examined with due regard to the facts and evidence concerning the Defendant's ownership, as well as its open and extensive use of the “CLASSIC” trademark since 1979. He submitted that the use of the “CLASSIC” trademark by the Defendant since 1979 is not in dispute at all. He submitted that JANVI's claim for authorship of the artistic work “CLASSIC” and its adoption as a mark in 1968, is wholly false and belied by the Plaint and her own documents. He submitted that JANVI, who was born only in the year 1987, claims that she adopted the “CLASSIC” label in the year 1968. This is an impossibility. She has next pleaded that she applied for trademark registration of this mark on 25th April 2012 and the same is pending. She has annexed two trademark applications, one in Class 34 and the other in Class 5 at Exhibit-B to the Plaint. Pertinently, both the applications are for registration of a label with the word “CLASSIC” in a stylized font. In respect of both these applications, JANVI has claimed to be the user of these marks since 1st January 1968. This apart, JANVI has also pleaded that she obtained the copyright registration for the label “CLASSIC” as an artistic work under Registration No. A-103201/2013 in 2012. A copy of the copyright registration and her application thereof is annexed at Exhibit-A to the Plaint. Mr. Kadam submitted that what is important to note is that before the Registrar of Copyright, JANVI has asserted on oath that she is an artist by profession, and she is the author of the “CLASSIC” artistic work and claimed it to be an unpublished work under the Copyright Act. Incidentally, the “CLASSIC” labels which are claimed to be in use since 1968 and the “CLASSIC” artistic work in respect of which the Plaintiff obtained copyright registration in 2012 is one and the same. Thus, the “CLASSIC” artistic work for which copyright protection was sought is also the same label that was purportedly adopted by JANVI in 1968 and for which reliefs for passing off have also been sought. In other words, the cause of action of copyright infringement and the cause of action of passing off pertains to the same “CLASSIC” label. It, therefore, stands to reason that by claiming authorship of the “CLASSIC” artistic work, JANVI asserts that she was the artist who conceived the “CLASSIC” artistic work and adopted the same as a mark in 1968. This is also confirmed from the Search Certificate issued from the trademark Registry under Rule 24(3) of the Trade Marks Rules, 2002 wherein it is certified that JANVI's own trademark is identical and/or similar to the artistic work applied for registration under the Copyright Act. Though the Defendant does not accept this Search Certificate, this claim has also been made by JANVI in a User Affidavit dated 16th April 2018.

11. Mr. Kadam submitted that ex-facie the Plaintiff's claim of authorship of the “CLASSIC” artistic work and adoption of the same as a mark in 1968, is clearly false considering that she was born on 21st April 1987 and was only 28 years old at the time of instituting the present Suit, a fact borne out from her affidavit in support of her claim. Further, she was 25 years old at the time of applying for the copyright registration in 2012. It is, therefore, impossible for her to claim authorship of the “CLASSIC” label and adoption of this mark in 1968 when she was only born in 1987.

12. Mr. Kadam submitted that when this impossibility was pointed out by the Defendant, the Plaintiff has now taken a contrary plea in the proceedings before this Court. She has stated on oath that the artistic work “CLASSIC” was invented, authored, and owned by her grandmother, Mrs. Damayanti Kantilal Shah in 1968. This plea is taken by the Plaintiff in paragraph 13 of her affidavit in reply dated 23rd January 2017 in Chamber Summons No. 868 of 2016 wherein she has averred that the copyright in the “CLASSIC” label existed since its creation in 1968 by Mrs. Damayanti Kantilal Shah i.e. her grandmother. Mr. Kadam pointed out that despite this, as recently as on 16th April 2018, JANVI has filed a User Affidavit in support of her trademark application No. 2836646 before the Trademark Registry wherein she asserts as follows:—

“…………. the above said mark has honestly and independently conceived, coined and adopted by me in January 1968.”

“3……….the above said trademark has been honestly and bonafide conceived and adopted by me on 1st January, 1968 and also the said trademark has been openly, continuously, extensively and uninterruptedly used by me with indicating the services of my company under the said mark.”

(emphasis supplied)

13. Mr. Kadam submitted that it is important to note that in the affidavit in reply dated 23rd January 2017 filed in Chamber Summons No. 868 of 2016, the Plaintiff states that the copyright existed since its creation in 1968 by her grandmother, Mrs. Damayanti Kantilal Shah. Despite this, later, on 16th April 2018, she represents to the trademark authorities that the said “CLASSIC” mark has honestly and independently been conceived, coined and adopted by her in January 1968. Looking at all this material, Mr. Kadam submitted that the following facts emerge which would negate JANVI's prospects of ever succeeding in her claim:

(a) In view of the fact that she was born in 1987, JANVI's case of authorship of the “CLASSIC” artistic work and adopting the same as a mark in 1968, is wholly false and untenable;

(b) JANVI's plea in her affidavit in reply dated 23rd January 2017 that Mrs. Damayanti Shah (her grandmother) was the original creator of the artistic work and adopter of the mark in 1968 is contrary to her original pleaded case in the Plaint that she had conceived the “CLASSIC” artistic work and the mark in 1968. It, therefore, also overwhelmingly proves the lack of veracity in JANVI's case and renders it apparent that her claim is fraudulent;

(c) JANVI's production of a purported transfer between Damayanti Shah to Jayant Shah and thereafter from Jayant Shah to the Plaintiff further weakens and makes bare the falsity of her own original case of being the original author of the artistic work and adopter of the same as a mark in 1968;

(d) The Plaintiff, Jayant Shah (her father) and Damayanti Shah (her grandmother) are all family members. It is inconceivable that the Plaintiff would not be aware of the history relating to the conception of the “CLASSIC” artistic work and its adoption as a mark. Rather, the constant changes in her pleas suggest a systematic attempt to improve her case. The constant changes in her story clearly goes to suggest that her whole claim is fraudulent and false.

14. Mr. Kadam therefore, submitted that the Plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding in her claim for copyright infringement.

15. Even as far as her claim for passing off is concerned, Mr. Kadam submitted that the facts of the present case would clearly establish that the Plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding even on this claim. He submitted that even otherwise the Plaintiff's claim for use of the trademark “CLASSIC” is fraudulent as her documents are tainted by gross fraud. He pointed out that the Plaintiff has purported to annexe copies of invoices/bills purportedly pertaining to sale of products from 1968 till date, at Exhibit-C to the Plaint. He submitted that looking at the aforesaid invoices, they are ex-facie fraudulent. He submitted that the bills which are annexed to the Plaint at pages 54 to 90 are purportedly issued by one M/s. Vikas Art Industries between the years 1968 till 2004. He submitted that interestingly each and every bill is dated between 1st January and 3rd January of each year, respectively. In other words, all the bills are either dated between 1st January to 3rd January of each year from 1968 to 2004.

16. Be that as it may, Mr. Kadam submitted that these invoices issued by M/s. Vikas Art Industries are irrelevant for the purposes of passing off since they do not relate to sales made by the Plaintiff but appear to be invoices issued out to it by one M/s. Vikas Art Industries. In any event, on the face of it, these bills appear to be ex-facie fraudulent. He submitted that it is a historical fact that India Post adopted the Postal Index Number Code System (Pin Codes) for posting correspondence only on 15th August 1972. In other words, Pin Codes were only assigned to regions from 15th August 1972. However, the bills of M/s. Vikas Art Industries produced by the Plaintiff show their address as 33A, Block-D, Old Nagardas Road, Andheri (E), Bombay-400 069. This same letterhead appears on all bills dated 1st January, 1968, 1st January, 1969, 1st January, 1970, 1st January, 1971 and 3rd January, 1972. Clearly, therefore, these invoices are pure fabrications and have been inserted only to bolster the Plaintiff's case. He submitted that this does not stop here. In fact, if one looks at the bills, the telephone number mentioned on those bills bears seven-digits. However, seven-digit telephone numbers were only adopted in India in or around 1980. Thus, it is wholly inconceivable for invoices purportedly issued in 1968 onwards till 1980 to bear a seven-digit telephone number. This clearly goes to show that these bills of M/s. Vikas Art Industries which are produced by the Plaintiff, apart from being irrelevant for the claim of passing off, are clearly false and fabricated and cannot be relied upon.

17. Mr. Kadam thereafter submitted that likewise, the purported invoices issued by the Plaintiff are also ex-facie fraudulent. To this, he brought to my attention pages 91 to 108 of the Plaint. These are invoices and receipts, all dated between the year 1968 to 1972. These invoices purportedly show sale of the Plaintiff's products to different entities such as Voltas Limited and M/s. Grand Hotel, Ballard Estate, amongst others. Mr. Kadam was at pains to point out that interestingly all these bills as well as the invoices have the stamp of JAYANT INDUSTRIES along with its address and the Pin Code showing Bombay - 400 028. Further, he pointed out that even the receipts issued (page 96 of the Plaint) show a seven-digit telephone number. Neither a Pin Code nor seven-digit telephone numbers existed in 1968. In fact, the Pin Codes were assigned to regions only in 1972 and seven-digit telephone numbers came into existence only some time in 1980. He, therefore, submitted that even the entire claim for passing off by the Plaintiff is based on wholly false and fabricated documents, and therefore, has to be rejected. In other words, he submitted that based on the documents produced, there is no scope for the Plaintiff to succeed in the present Suit, and therefore, the Defendant is entitled to a Summary Judgment of dismissal as contemplated under Order XIII-A of the CPC.

18. Mr. Kadam also pointed out that apart from this fabrication, to improve the case of the Plaintiff, there has been further interpolation and fabrication indulged by the Plaintiff. In this regard, he brought to my attention the affidavit of Damayanti K. Shah which was produced to substantiate the case of the Plaintiff that her grandmother was the author of the “CLASSIC” artistic work and adopted the same in 1968. Mr. Kadam pointed out that when the impossibility of the Plaintiff's authorship was brought to the attention of the Plaintiff, to counter this insurmountable difficulty, the Plaintiff set up an opposing case that her grandmother is the inventor/creator of the artistic work “CLASSIC”, and which was adopted in 1968. This case was set up in the affidavit in support filed in Notice of Motion No. 295 of 2016. In this affidavit she also annexed a document dated 1st January 1969 purportedly executed by her grandmother titled as “an affidavit and deed for confirmation of declaration made one year back”. This declaration was done to somehow anchor the date of adoption of the artistic work “CLASSIC” in 1968. Again, this affidavit-cum-declaration, which is dated 1st January 1969 has a stamp of JAYANT INDUSTRIES with a Pin Code on it of Bombay - 400028. It is inconceivable that an affidavit that was executed in 1969, has a stamp of a company with a Pin Code which was assigned to different regions of the city only in the year 1972. He submitted that this does not stop here. Pertinently, the same purported affidavit-cum-declaration is also now produced in the affidavit in reply dated 9th December 2020 to the present Interim Application. A bare comparison of the two relevant pages of the purported affidavit-cum-declaration produced in Notice of Motion No. 295 of 2016 and the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in the affidavit in reply dated 9th December 2020, it is clear that there is an interpolation in the purported affidavit-cum-declaration. He submitted that the same is ex-facie clear as there are things that are written by hand in the affidavit-cum-declaration produced now which were absent in the same affidavit-cum-declaration produced in the year 2016. In the affidavit-cum-declaration produced now, a date is mentioned of 22nd January 1973 so as to somehow explain the Pin Code appearing on the affidavit-cum-declaration. He submitted that this too would go to show that the Plaintiff has approached this Court with a completely false case and the Defendant would therefore be entitled to a Summary Judgment of dismissal under Order XIII-A of the CPC. For all the aforesaid reasons, Mr. Kadam submitted that the above Interim Application be allowed with compensatory costs. Mr. Kadam has also produced a break up of costs incurred by the Defendant in defending this litigation amounting to a sum of Rs. 1,19,26,308/-. This has been produced along with the written submissions tendered on behalf of the Defendant.

19. On the other hand, Ms. Khatri, the learned counsel appearing on behalf of the Plaintiff, submitted that in the Plaint, the Plaintiff is seeking reliefs under the Copyright Act. She submitted that a copyright secures creative or intellectual creations and the creator, inventor, assignee has rights to use the said creative and intellectual creation under the Copyright Act, 1957. The protection given under the Copyright Act is to prevent others from using the creation without the owner's consent. She submitted in the facts of the present case, late Mrs. Damayanti K Shah (grandmother of the Plaintiff) is the creator, inventor, and owner of the artistic work “CLASSIC”. Since 1968, the grandmother is using the said artistic work, which is her creation. In the year 1982, when she retired from JAYANT INDUSTRIES (which was a partnership firm at that time), she gave her stake to her son Mr. Jayant K. Shah (father of the Plaintiff - JANVI). In turn, Jayant K. Shah has transferred all his rights to the Plaintiff in the year 2007. It is in these circumstances, that JANVI has become the sole proprietor of JAYANT INDUSTRIES. Ms. Khatri pointed out that as per Section 18(2) of the Copyright Act, JANVI became the owner of the copyright. Since she became the owner, she could apply for registration which was her grandmother's creation, and it is in these circumstances that she applied for copyright registration and obtained the same. She submitted that it is important to note that no one opposed the registration of the copyright of the Plaintiff. She submitted that this was because the Defendant wanted to buy the artistic work “CLASSIC” created by her grandmother. She submitted that in fact there is lengthy correspondence annexed to the Plaint which would substantiate this fact. She submitted that several emails were exchanged in this regard between the father of the Plaintiff and the Defendant. However, after Mr. Jayant K. Shah's (father of the Plaintiff) emails were hacked, his several emails were deleted where he had a conversation with the Defendant. He sent a notice to the Defendant to show soft copies of these emails where according to the Plaintiff, the Defendant had agreed to buy the Plaintiff's artistic work, but the Defendant declined to do so. It was in these circumstances that a cease-and-desist notice dated 14th August, 2014 was sent to the Defendant and to which also there was no reply. Finally, therefore, the Plaintiff was constrained to file the present Suit. She, therefore, submitted that the Plaintiff being the owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC”, which is being used by the Defendant without her consent, the Plaintiff is entitled to the reliefs claimed in the Plaint. She submitted that it is wholly incorrect on the part of Mr. Kadam to submit that the Plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding in the present Suit. As far as the claim of Rs. 2,100 Crores is concerned, Ms. Khatri submitted that as per Section 55 of the Copyright Act, the Plaintiff seeks relief for damages and rendition of accounts. She submitted that Section 55 contemplates that where copyright in any work has been infringed, the owner of the copyright shall, except as otherwise provided by the Act, be entitled to all such remedies by way of injunction, damages, accounts and otherwise as are or may be conferred by law for the infringement of such right. She therefore submitted that this is a specific remedy that the Plaintiff is entitled to invoke under the provisions of the Copyright Act and hence a claim is made for the sum of Rs. 2,100 Crores. For all the aforesaid reasons, Ms. Khatri submitted that there is no merit in the above Interim Application and the same be dismissed with compensatory costs.

20. I have heard the learned counsel for the parties at length and have carefully perused the papers and proceedings in the present Suit as well as the Interim Application. Before I deal with the facts of the case, it would be apposite to understand why the provisions of Order XIII-A of the CPC were brought into force. The aforesaid provision was brought into force by the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. The aforesaid Act (Commercial Courts Act, 2015) was brought on the statute book pursuant to the recommendations contained in the 253rd report of the Law Commission of India. The Law Commission inter alia recommended a streamlined procedure to be adopted for the conduct of cases in the Commercial Division and in the Commercial Court by amending the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 so as to improve the efficiency and reduce delays in disposal of commercial cases. The Commission recommended that the amended CPC as applicable to the Commercial Divisions and Commercial Courts should prevail over the existing High Court rules and other provisions of the CPC to the contrary. Some of the important changes proposed to the CPC (amongst others) were (i) that a new procedure for “summary judgment” be introduced to permit the Courts to decide a claim pertaining to any Commercial Dispute without recording oral evidence, as long as the application for summary judgment was filed before the framing of issues. The Commission further recommended that Courts also be empowered to make “conditional orders” wherever necessary; and (ii) a new costs regime of “costs to follow event” be introduced, with elaborate directions on what constitutes “costs” and the circumstances the Courts should have regard to while making an order on costs. The recommendation of the Commission on the issue of “costs” was inter alia based on a decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Subroto Roy Sahara v. Union of India [(2014) 8 SCC 470] wherein the Supreme Court clearly opined that the innocent suffering litigant spends valuable time briefing counsel and preparing them for his claim, and the time, which he should have spent at work or with his family, is lost for no fault of his. The Supreme Court, therefore, suggested to the legislature that the litigant who has succeeded must be compensated by the one who has lost. The suggestion to the legislature was to formulate a mechanism that anyone who initiates and continues a litigation senselessly, pays for the same. Acting on the recommendations of the Law Commission, the Government introduced a Bill in Parliament namely, the Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Bill of 2015. As per this Bill, all suits, appeals, or applications relating to commercial disputes of a Specified Value were to be dealt with by the Commercial Courts or the Commercial Division of the High Court. This Bill was then made into an Act, namely, The Commercial Courts, Commercial Division and Commercial Appellate Division of High Courts Act, 2015. Thereafter, the name of the Act was changed to The Commercial Courts Act, 2015 w.r.e.f 03-05-2018. Section 16 of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 brought about amendments to the CPC and inter alia stipulated that the provisions of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 (5 of 1908) shall, in their application to any suit in respect of a commercial dispute of a Specified Value, shall stand amended in the manner as specified in the Schedule to the said Act. One such amendment was to Section 35 of the CPC which relates to awarding costs and the other was the introduction of Order XIII-A empowering the Court to pass summary judgment without recording evidence in certain circumstances. This is how Order XIII-A was brought on the statute book. For the sake of convenience, Order XIII-A is reproduced hereunder:—

“ORDER XIII-A

Summary Judgment

1. Scope of and classes of suits to which this order applies.—

(1) This order sets out the procedure by which courts may decide a claim pertaining to any Commercial Dispute without recording oral evidence.

(2) For the purposes of this order, the word “claim” shall include—

(a) part of a claim;

(b) any particular question on which the claim (whether in whole or in part) depends; or

(c) a counter-claim, as the case may be.

(3) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary, an application for summary judgment under this order shall not be made in a suit in respect of any Commercial Dispute that is originally filed as a summary suit under Order XXXVII.

2. Stage for application for summary judgment.—An applicant may apply for summary judgment at any time after summons has been served on the defendant:

Provided that, no application for summary judgment may be made by such applicant after the court has framed the issues in respect of the suit.

3. Grounds for summary judgment.—The court may give a summary judgment against a plaintiff or defendant on a claim if it considers that—

(a) the plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding on the claim or the defendant has no real prospect of successfully defending the claim, as the case may be; and

(b) there is no other compelling reason why the claim should not be disposed of before recording of oral evidence.

4. Procedure.—(1) An application for summary judgment to a court shall, in addition to any other matters the applicant may deem relevant, include the matters set forth in sub-clauses (a) to (f) mentioned hereunder:

(a) the application must contain a statement that it is an application for summary judgment made under this order;

(b) the application must precisely disclose all material facts and identify the point of law, if any;

(c) in the event the applicant seeks to rely upon any documentary evidence, the applicant must,—

(i) include such documentary evidence in its application, and

(ii) identify the relevant content of such documentary evidence on which the applicant relies;

(d) the application must state the reason why there are no real prospects of succeeding on the claim or defending the claim, as the case may be;

(e) the application must state what relief the applicant is seeking and briefly state the grounds for seeking such relief.

(2) Where a hearing for summary judgment is fixed, the respondent must be given at least thirty days' notice of—

(a) the date fixed for the hearing; and

(b) the claim that is proposed to be decided by the court at such hearing.

(3) The respondent may, within thirty days of the receipt of notice of application of summary judgment or notice of hearing (whichever is earlier), file a reply addressing the matters set forth in clauses (a) to (f) mentioned hereunder in addition to any other matters that the respondent may deem relevant:

(a) the reply must precisely—

(i) disclose all material facts;

(ii) identify the point of law, if any; and

(iii) state the reasons why the relief sought by the applicant should not be granted;

(b) in the event the respondent seeks to rely upon any documentary evidence in its reply, the respondent must—

(i) include such documentary evidence in its reply; and

(ii) identify the relevant content of such documentary evidence on which the respondent relies;

(c) the reply must state the reason why there are real prospects of succeeding on the claim or defending the claim, as the case may be;

(d) the reply must concisely state the issues that should be framed for trial;

(e) the reply must identify what further evidence shall be brought on record at trial that could not be brought on record at the stage of summary judgment; and

(f) the reply must state why, in light of the evidence or material on record if any, the Court should not proceed to summary judgment.

5. Evidence for hearing of summary judgment.—(1) Notwithstanding anything in this order, if the respondent in an application for summary judgment wishes to rely on additional documentary evidence during the hearing, the respondent must:

(a) file such documentary evidence; and

(b) serve copies of such documentary evidence on every other party to the application at least fifteen days prior to the date of the hearing.

(2) Notwithstanding anything in this order, if the applicant for summary judgment wishes to rely on documentary evidence in reply to the defendant's documentary evidence, the applicant must:

(a) file such documentary evidence in reply; and

(b) serve a copy of such documentary evidence on the respondent at least five days prior to the date of the hearing.

(3) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary, sub-rules (1) and (2) shall not require documentary evidence to be:

(a) filed if such documentary evidence has already been filed; or

(b) served on a party on whom it has already been served.

6. Orders that may be made by court.—(1) On an application made under this order, the court may make such orders that it may deem fit in its discretion including the following—

(a) judgment on the claim;

(b) conditional order in accordance with Rule 7 mentioned hereunder;

(c) dismissing the application;

(d) dismissing part of the claim and a judgment on part of the claim that is not dismissed;

(e) striking out the pleadings (whether in whole or in part); or

(f) further directions to proceed for case management under Order XV-A.

(2) Where the court makes any of the orders as set forth in sub-rule (1)(a) to (f), the court shall record its reasons for making such order.

7. Conditional order.—(1) Where it appears to the court that it is possible that a claim or defence may succeed but it is improbable that it shall do so, the court may make a conditional order as set forth in Rule 6(1)(b) above.

(2) Where the court makes a conditional order, it may:

(a) make it subject to all or any of the following conditions:

(i) require a party to deposit a sum of money in the court;

(ii) require a party to take a specified step in relation to the claim or defence, as the case may be;

(iii) require a party, as the case may be, to give such security or provide such surety for restitution of costs as the court deems fit and proper;

(iv) impose such other conditions, including providing security for restitution of losses that any party is likely to suffer during the pendency of the suit, as the court may deem fit in its discretion; and

(b) specify the consequences of the failure to comply with the conditional order, including passing a judgment against the party that have not complied with the conditional order.

8. Power to impose costs.—The court may make an order for payment of costs in an application for summary judgment in accordance with the provisions of Sections 35 and 35-A of the Code.”

21. I must, at the very outset, state that I have no hesitation in holding that the Plaintiff has come to this Court with a completely false case and to bolster it, has relied upon forged and fabricated documents. As mentioned earlier, the Plaintiff seeks perpetual orders of injunction, restraining the Defendant from in any manner using in relation to cigarettes or any other products, the impugned trademark, or any other trademark identical with and/or deceptively similar to the Plaintiff's trademark and copyright “CLASSIC’. A fanciful claim of Rs. 2,100 crores by way of damages and/or royalty is also made in the Plaint. The Plaintiff has come to Court with a case that JAYANT INDUSTRIES was initially established as a partnership firm with Mrs. Damayanti Kantilal Shah and her husband Kantilal G. Shah as being the partners. Mrs. Damayanti Shah continued to act as a partner of the said firm till her retirement in 1982 and upon her retirement, gave her stake to Mr. Jayant Kantilal Shah, who is the father of the Plaintiff - JANVI. At some point, Jayant Kantilal Shah (her father) as well as Mr. Kantilal Shah (her grandfather), during their lifetime, gave their entire stake in JAYANT INDUSTRIES directly to JANVI sometime in the year 2007. It is on this basis that JANVI claims to be a sole proprietor of JAYANT INDUSTRIES. What is important to note is that in the Plaint, it is JANVI's case that the business of the Plaintiff has been carried on for the last several generations, spread over decades since 1968. It is stated in the Plaint that she is the author and owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” written in a stylized form of which the word “CLASSIC’ forms an essential and prominent part. In other words, in the Plaint, the Plaintiff asserts that she is the author and owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC”. Thus, the entire cause of action in the Plaint relating to copyright is based on the fact that JANVI is the author and owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC”. However, it is an admitted fact that the Plaintiff - JANVI was born only on 21st April 1987. I, therefore, fail to understand how JANVI could claim to be the author and owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” from 1968 when she was born in the year 1987. Initially, this was sought to be explained by stating before me that this was an inadvertent mistake and that the real author was the grandmother (Damayanti Kantilal Shah), and JANVI has become the owner of the copyright as the entire business of JAYANT INDUSTRIES was transferred to her. In the first instance, this explanation seemed plausible, but Mr. Kadam rightly pointed out that one can understand a mistake in the Plaint, but in several other documents filed before the authorities under the Trade Marks Act, 1999 as well as the Copyright Act, 1957, JANVI re-asserts that she is the author and owner of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC”. One such document can be found at Exhibit-A, which is an extract from the Register of Copyright dated 13th August 2013 (Page 36 of the Plaint). In this extract, it is shown that the name, address and nationality of the applicant is JAYANT INDUSTRIES, and the applicant is the owner in the copyright of the work. The class and description of the work is shown as artistic work and the title of the work is “CLASSIC LOGO”. Thereafter, against the heading, ‘Name, address and nationality of the author and if the author is deceased, date of his decease’, it is mentioned “Ms. Janvi Jayant Shah, Jayant Industries…..” Thereafter, in the column whether the work is published or unpublished, it is represented that the same is unpublished. What is important to note is that even before the authorities under the Copyright Act, it is represented that JANVI is the author of the artistic work “CLASSIC”. Even in the No Objection Certificate (page 43 of the plaint) and which was submitted to the authorities under the Copyright Act, JANVI states that she is an Artist by profession and that she is the author of the artistic work titled “CLASSIC”. Even before the Trade Mark authorities, and where an application was made to register “CLASSIC” as a trademark in Class 05 (page 51 of the Plaint), it is stated that the said mark is being used since January, 1984 in respect of the provisions mentioned therein. From looking at these two documents and referred to by me earlier, two things emerge : (i) JANVI claims to be the author of the artistic work in “CLASSIC” and (ii) she has been using the same as a trademark since the year 1984. I must mention that an application has thereafter been made before the Trade Mark authorities to change the user date from 1st January, 1984 to 1st January, 1968. Be that as it may, the Plaintiff - JANVI has come to Court with a specific case, namely, that she is the author of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” and not anyone else. She also claims that the said artistic work has been in use since 1968. This is an impossibility. She can never be the author of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” from 1968 when she was born only in the year 1987. This can only mean one of two things : (i) if the Plaintiff is the author, then the artistic work “CLASSIC” could never have been in use from 1968; or (ii) if the artistic work “CLASSIC” was in use from 1968, the Plaintiff - JANVI could never be the author. It is, therefore, clear that the Plaintiff has come to Court with a completely false case. This was now sought to be explained by changing the entire case and contending that Mrs. Damayanti K. Shah (the grandmother of the Plaintiff) was the creator, inventor, and the owner of the artistic mark “CLASSIC” and that she had been using the same from 1968. This changes the entire nature of the case. It would, therefore, stand to reason that the Plaint, as it stands, can never succeed on the cause of action of copyright infringement because the Plaintiff has come to Court with a specific case that she is the author and owner of the copyright and has been in extensive use of the same since the year 1968, even though she was born only in the year 1987.

22. Even on the cause of action for passing off, the Plaintiff is guilty of wholesale fabrication. In this regard, it is important to see the bills which are annexed to the Plaint at pages 54 to 90 and purportedly issued by one M/s. Vikas Art Industries between the years 1968 to 2004. Apart from the fact that most of these bills are dated between 1st January to 3rd January of each year respectively, these bills, at least till the year 1980, appear to be fabricated or, at the very least, back-dated. On page 54 of the Plaint is one such bill. It is on the letterhead of M/s. Vikas Art Industries wherein the factory telephone number is shown as 8326275 and the office telephone number is shown as 3443352. The address shown is 33 A, Block B, Old Nagardas Road, Andheri (East), Bombay - 400 069. The bill at page 54, and which I have adverted to, is dated 1st January 1968. What is very important to note is that India Post adopted the Postal Index Number Code system (Pin Codes) only on 15th August 1972. In other words, Pin Codes were only assigned to regions from 15th August 1972. I, therefore, fail to understand how the letterhead of M/s. Vikas Art Industries shows a Pin Code of 400 069, when the bill is dated 1st January 1968. This itself will go to show that, at the very least, the aforesaid bill is back-dated and procured only for the purposes of the present litigation. Furthermore, as stated earlier, the letterhead of M/s. Vikas Art Industries sets out the factory telephone number as 8326275 and the office telephone number as 3443352. I am surprised that this bill purportedly issued by M/s. Vikas Art Industries on 1st January 1968 has seven-digit telephone numbers when in fact, seven-digit telephone numbers were adopted in India only in and around the year 1980. Thus, it is wholly inconceivable for the invoices/bills purportedly issued by M/s. Vikas Art Industries from 1968 to 1979, to bear seven-digit telephone numbers. This is yet another factor which goes to show that the bills produced from pages 54 to 90 of the Plaint are false and fabricated, or at the very least back-dated, and procured only for the purposes of the present Suit. In fact, I have no hesitation in saying that if one looks at all the bills, [i.e. the bills starting from 1st January 1968 to the year 2004 (pages 54 to 90 of the Plaint)], they all appear to be written in the exact same handwriting and in the exact same format. It appears that all these bills have been written at one and the same time and by the same person.

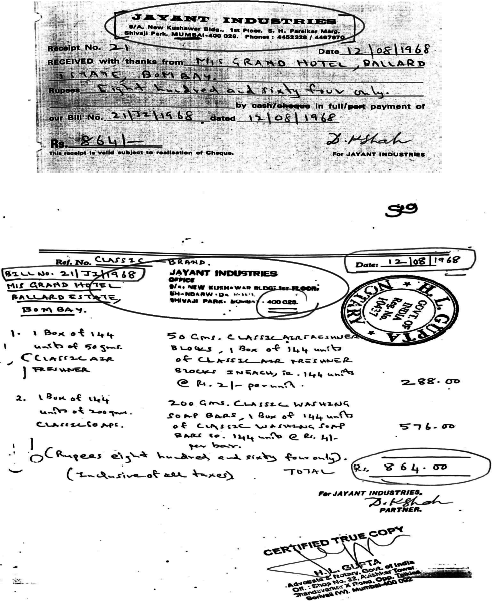

23. I must mention that since the bills purportedly issued by M/s. Vikas Art Industries [pages 54 to 90 of the Plaint] only show labour charges for the “CLASSIC” cigarette ash-trays, these bills do not really bolster the case of the Plaintiff from the point of view of passing off. To show sales purportedly done by the Plaintiff, she has annexed bills/invoices which can be found from pages 91 to 108 of the Plaint. As one example, there is a bill/invoice dated 12th August 1968, which is issued by the Plaintiff to M/s. Grand Hotel, Ballard Estate, Bombay (page 99 of the Plaint). Under this invoice/bill, the Plaintiff purportedly sells certain “CLASSIC” air-fresheners and washing soap bars to M/s. Grand Hotel. This invoice bears the stamp of the Plaintiff “Jayant Industries” with an address showing the Pin Code “Bombay 400 028”. Once again, as mentioned earlier, Pin Codes were assigned to regions by India Post only on 15th August 1972. I fail to understand how a bill of 12th August 1968 has the stamp of JAYANT INDUSTRIES showing its address with a Pin Code “Bombay 400 028” when Pin Codes were never in existence at that time. When I asked the Plaintiff to explain this, the answer given across the bar was that the Plaintiff's father had put the stamp of JAYANT INDUSTRIES after 15th August 1972. As to why he had put this stamp at a later date and that too four years after the issuance of the bill, he had no explanation. Clearly, the Plaintiff is lying to the Court. What is important to note is that for this very bill, the Plaintiff has purportedly issued a receipt to M/s. Grand Hotel, Ballard Estate, Bombay. This receipt is also dated 12th August 1968 (page 96 of the Plaint). More importantly, the receipt does not bear a stamp, but on the top of the receipt, it is printed as follows:

“JAYANT INDUSTRIES

9/A, New Kushawar Bldg., 1st Floor, S.H. Parelkar Marg, Shivaji Park, MUMBAI - 400 028. Phones : 4452328/4467970”

24. On this receipt, there is no question of putting any stamp. The above reproduction is printed on the receipt. Here too, a Pin Code of 400 028 is shown which came into effect only on or after 15th August 1972. Further, seven-digit telephone numbers are shown, which came only in and around the year 1980. What is even more glaring is that the address is shown as “…..MUMBAI - 400 028”. However, “BOMBAY” became “MUMBAI” only sometime in the year 1995. Therefore, how a receipt dated 12th August 1968 could bear a Pin Code on the address; seven-digit telephone numbers; and “MUMBAI” instead of “BOMBAY”; is beyond my comprehension. I have no hesitation in saying that this is wholesale fabrication. I have given this only as an illustration as all the bills/invoices and whatever receipts are produced in the Plaint are tainted with the same fabrication. The bill and the receipt issued to Grand Hotel are reproduced hereunder (oval border supplied by me):

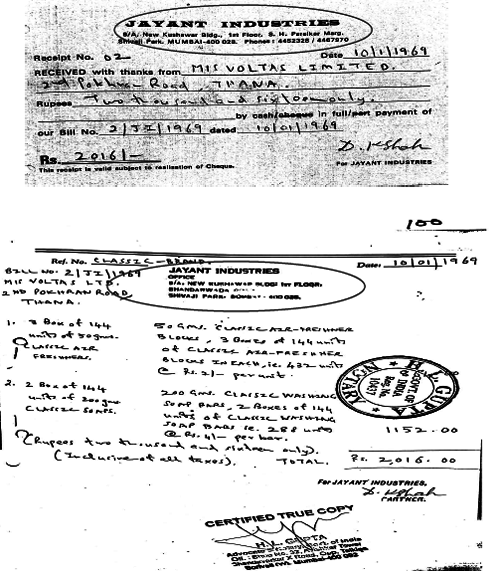

25. As another illustration, one other such receipt can be found on page 98 of the Plaint which was issued to M/s. Voltas Limited and the date of the receipt is 10th January, 1969. This receipt was issued with reference to a bill which can be found on page 100 of the Plaint. These are also reproduced hereunder (oval border supplied by me):

26. After carefully going through the bills and receipts annexed to the Plaint, I have no hesitation in holding that the aforesaid bills and receipts purportedly showing the user of the artistic work “CLASSIC” from 1968 onwards are fabricated, or at the very least, back-dated to somehow establish the user of the artistic work “CLASSIC” from a date prior to the user of the mark “CLASSIC” by the Defendant. On the basis of these fabricated documents/back-dated documents, I am clearly of the view that the claim by the Plaintiff for passing off can never succeed.

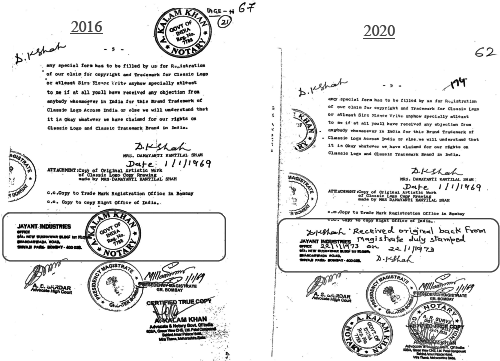

27. There is one more fabrication that the Plaintiff is guilty of. As mentioned earlier, when the impossibility of the Plaintiff's case was set up by the Defendant, namely, that she could never be the author of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” from 1968 since she was born only in 1987, the Plaintiff, to bolster its case, filed an affidavit in Notice of Motion No. 295 of 2016. In this affidavit, a document dated 1st January 1969 purportedly executed by the Plaintiff's grandmother titled as “An affidavit and Deed for Confirmation of Declaration made one year back” was also annexed. It appears that this declaration was done to somehow anchor the date of adoption of the artistic work “CLASSIC” in the year 1968. This affidavit-cum-declaration, which is dated 1st January 1969, has a stamp of JAYANT INDUSTRIES with a Pin Code on it “Bombay - 400 028.” It is inconceivable that an affidavit that was executed in 1969, has a stamp of the Plaintiff's address with a Pin Code and which was assigned only on or after the year 1972. However, this does not stop here. To get over this insurmountable difficulty, the purported affidavit-cum-declaration is now also produced in the affidavit-in-reply to the above Interim Application dated 9th December 2020. The last page of the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in the Affidavit in Support of Notice of Motion No. 295 of 2016 and the last page of the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in the affidavit-in-reply dated 9th December 2020 is set out hereunder (rectangular border & Year supplied by me):

28. On a bare comparison of the aforesaid two pages, it is clear that there is an interpolation in the purported affidavit-cum-declaration. It is ex-facie clear that there are things that are written by hand in the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in 2020, which were absent in the one produced in the year 2016. In the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in 2020, a date of 22nd January 1973 is mentioned. This is to somehow explain the Pin Code appearing in the affidavit-cum-declaration. Looking at these two pages, I asked the Constituted Attorney of the Plaintiff (her father) to explain why there was a difference in the affidavit-cum-declaration produced in the year 2016 and the one produced in 2020. Ironically, the answer given was that whilst taking a photocopy in 2016, the xerox operator must have blanked out what is written by hand in the affidavit-cum-declaration. When asked as to why a xerox operator would blank out the handwritten portion, he had absolutely no answer. The only answer, and which I thought was absolutely ludicrous, is that:“Sir I have many enemies”. I find this explanation to be wholly ludicrous for more than one reason. Firstly, I cannot understand why an ordinary xerox operator would be the enemy of the Plaintiff's Constituted Attorney. Secondly, even if one were to assume what he says is true, it would not be easy to blank out what is handwritten. It would have to be cut in a specific way so as to ensure that the stamp of the Plaintiff remains, but the handwritten portion is covered up. I therefore have no hesitation in holding that the Plaintiff is not only being dishonest but has come to Court with a completely false case. It is now well settled that when a party comes to Court with a false case, he can be shown the door at any stage of the proceedings. If one needs any authority on this subject, a decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Chengalvaraya Naidu by LRs v. Jagannath by LRs [(1994) 1 SCC 1], would suffice. The relevant portion of this decision reads thus:

“5. The High Court, in our view, fell into patent error. The short question before the High Court was whether in the facts and circumstances of this case, Jagannath obtained the preliminary decree by playing fraud on the court. The High Court, however, went haywire and made observations which are wholly perverse. We do not agree with the High Court that “there is no legal duty cast upon the plaintiff to come to court with a true case and prove it by true evidence”. The principle of “finality of litigation” cannot be pressed to the extent of such an absurdity that it becomes an engine of fraud in the hands of dishonest litigants. The courts of law are meant for imparting justice between the parties. One who comes to the court, must come with clean hands. We are constrained to say that more often than not, process of the court is being abused. Property-grabbers, taxevaders, bank-loan-dodgers and other unscrupulous persons from all walks of life find the court-process a convenient lever to retain the illegal gains indefinitely. We have no hesitation to say that a person, who's case is based on falsehood, has no right to approach the court. He can be summarily thrown out at any stage of the litigation.”

(emphasis supplied)

29. This proposition was then again reiterated by the Supreme Court in the case of Indian Council for Enviro-Legal Action v. Union of India [(2011) 8 SCC 161]. In this decision, the Supreme Court inter alia opined that the Court should never permit a litigant to perpetuate illegality by abusing the legal process. It is the bounden duty of the Court to ensure that dishonesty and any attempt to abuse the legal process must be effectively curbed and the Court must ensure that there is no wrongful, unauthorised or unjust gain for anyone by the abuse of the process of the Court. The Supreme Court also held that one way to curb this tendency is to impose realistic costs which the defendant has in fact incurred in order to defend itself in the legal proceedings. The relevant portion of this decision reads thus:—

“191. In consonance with the principles of equity, justice and good conscience Judges should ensure that the legal process is not abused by the litigants in any manner. The court should never permit a litigant to perpetuate illegality by abusing the legal process. It is the bounden duty of the court to ensure that dishonesty and any attempt to abuse the legal process must be effectively curbed and the court must ensure that there is no wrongful, unauthorised or unjust gain for anyone by the abuse of the process of the court. One way to curb this tendency is to impose realistic costs, which the respondent or the defendant has in fact incurred in order to defend himself in the legal proceedings. The courts would be fully justified even imposing punitive costs where legal process has been abused. No one should be permitted to use the judicial process for earning undeserved gains or unjust profits. The court must effectively discourage fraudulent, unscrupulous and dishonest litigation.

192. The court's constant endeavour must be to ensure that everyone gets just and fair treatment. The court while rendering justice must adopt a pragmatic approach and in appropriate cases realistic costs and compensation be ordered in order to discourage dishonest litigation. The object and true meaning of the concept of restitution cannot be achieved or accomplished unless the courts adopt a pragmatic approach in dealing with the cases.

193. This Court in a very recent case Ramrameshwari Devi v. Nirmala Devi [(2011) 8 SCC 249] had an occasion to deal with similar questions of law regarding imposition of realistic costs and restitution. One of us (Bhandari, J.) was the author of the judgment. It was observed in that case as under : (SCC pp. 268-69, paras 54-55)

“54. While if mposing costs we have to take into consideration pragmatic realities and be realistic as to what the defendants or the respondents had to actually incur in contesting the litigation before different courts. We have to also broadly take into consideration the prevalent fee structure of the lawyers and other miscellaneous expenses which have to be incurred towards drafting and filing of the counter-affidavit, miscellaneous charges towards typing, photocopying, court fee, etc.

55. The other factor which should not be forgotten while imposing costs is for how long the defendants or respondents were compelled to contest and defend the litigation in various courts. The appellants in the instant case have harassed the respondents to the hilt for four decades in a totally frivolous and dishonest litigation in various courts. The appellants have also wasted judicial time of the various courts for the last 40 years.””

(emphasis supplied)

30. I must mention that though the learned advocate appearing on behalf of the Plaintiff canvassed arguments to the effect that the author of the copyright in the artistic work “CLASSIC” is the grandmother of the Plaintiff - JANVI and not JANVI herself, none of the documents or pleadings in the Plaint support her case. In view of the detailed discussion set out earlier in this judgment I am clearly of the view that the Plaintiff has approached this Court with a completely false case. These entire proceedings are nothing short of an abuse of the process of the Court. I have no hesitation in saying that these proceedings have been filed only to try and extract monies from the Defendant. It's what I would call a nuisance litigation. The Plaintiff has no real prospect of succeeding in the above Suit and I find no other compelling reason why the above Suit cannot be disposed of before recording oral evidence. I am, therefore, clearly of the view that the Defendant is entitled to a summary judgment of dismissal of the above Suit under the provisions of Order XIII-A of the CPC.

31. This now leaves me to deal with the issue of costs. Rule 8 of Order XIII-A of the CPC empowers the Court to impose costs and stipulates that the Court may make an order for payment of costs in an application for summary judgment in accordance with the provisions of Section 35 and 35-A of the CPC. Section 35, in so far as its application to a commercial dispute is concerned, reads thus:

“35. Costs.—(1) In relation to any commercial dispute, the court, notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force or rule, has the discretion to determine:

(a) whether costs are payable by one party to another;

(b) the quantum of those costs; and

(c) when they are to be paid.

Explanation.—For the purpose of clause (a), the expression “costs” shall mean reasonable costs relating to—

(i) the fees and expenses of the witnesses incurred;

(ii) legal fees and expenses incurred;

(iii) any other expenses incurred in connection with the proceedings.

(2) If the court decides to make an order for payment of costs, the general rule is that the unsuccessful party shall be ordered to pay the costs of the successful party:

Provided that the court may make an order deviating from the general rule for reasons to be recorded in writing.

Illustration

The plaintiff, in his suit, seeks a money decree for breach of contract, and damages. The court holds that the plaintiff is entitled to the money decree. However, it returns a finding that the claim for damages is frivolous and vexatious.

In such circumstances the court may impose costs on the plaintiff, despite the plaintiff being the successful party, for having raised frivolous claims for damages.

(3) In making an order for the payment of costs, the court shall have regard to the following circumstances, including—

(a) the conduct of the parties;

(b) whether a party has succeeded on part of its case, even if that party has not been wholly successful;

(c) whether the party had made a frivolous counter-claim leading to delay in the disposal of the case;

(d) whether any reasonable offer to settle is made by a party and unreasonably refused by the other party; and

(e) whether the party had made a frivolous claim and instituted a vexatious proceeding wasting the time of the court.

(4) The orders which the court may make under this provision include an order that a party must pay—

(a) a proportion of another party's costs;

(b) a stated amount in respect of another party's costs;

(c) costs from or until a certain date;

(d) costs incurred before proceedings have begun;

(e) costs relating to particular steps taken in the proceedings;

(f) costs relating to a distinct part of the proceedings; and

(g) interest on costs from or until a certain date.”

32. As far as the application of the provisions of costs to a commercial dispute is concerned, Section 35(1) stipulates that in relation to any commercial dispute, the Court, notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force or rule, has the discretion to determine (a) whether costs are payable by one party to another; (b) the quantum of those costs; and (c) when they are to be paid. There is also an Explanation to the said Section which clarifies that “costs” shall mean reasonable costs relating to : (i) the fees and expenses of the witnesses incurred; (ii) legal fees and expenses incurred; and (iii) any other expenses incurred in connection with the proceedings. Subsection 2 of Section 35 contemplates that if the Court decides to make an order for payment of costs, the general rule is that the unsuccessful party will be ordered to pay the costs of the successful party. Section 35(3) sets out the factors that the Court should consider whilst granting/awarding costs. One such factor is the conduct of the parties, and the other (amongst others) is also whether the party had made a frivolous claim and instituted a vexatious proceeding wasting the time of the Court.

33. In the facts of the present case, the conduct of the Plaintiff is reprehensible, to say the least. As mentioned earlier, she has approached this Court, not only with a false case and on the basis of dubious documents, but also lied to the Court. I have no hesitation in saying that the claims made in the above suit are wholly frivolous. In these circumstances, I would be justified in directing the Plaintiff to bear the entire costs incurred by the Defendant in defending this frivolous litigation. The advocates for the Defendant have quantified their costs at Rs. 1,19,26,308/-, the breakup of which is given at Exhibit-D to the Written Submissions filed by the Defendant. These costs mainly include fees paid to the advocates and counsel in various proceedings in the above Suit. Though the Plaintiff does not deserve any sympathy of this Court, considering that the Plaintiff is a lady, who is approximately 34 years old, purely out of mercy, I am of the view that the Plaintiff should pay to the Defendant costs quantified at Rs. 60 Lakhs.

34. In these circumstances, the following order is passed:—

(a) The above Suit is hereby dismissed;

(b) The Plaintiff is directed to pay costs of the above litigation of Rs. 60,00,000/- to the Defendant;

(c) The costs are directed to be paid within a period of four weeks from today, failing which the Defendant shall be at liberty to recover these costs as arrears of land revenue.

35. The above Interim Application as well as the above Suit are disposed of in the aforesaid terms. In view of this order, nothing survives in the above Chamber Summons and the same is disposed of accordingly.

36. This order will be digitally signed by the Private Secretary/Personal Assistant of this Court. All concerned will act on production by fax or email of a digitally signed copy of this order.

Print Page

No comments:

Post a Comment